Reflections on the 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics: Innovation-Driven Growth and the Political Economy of Creative Destruction

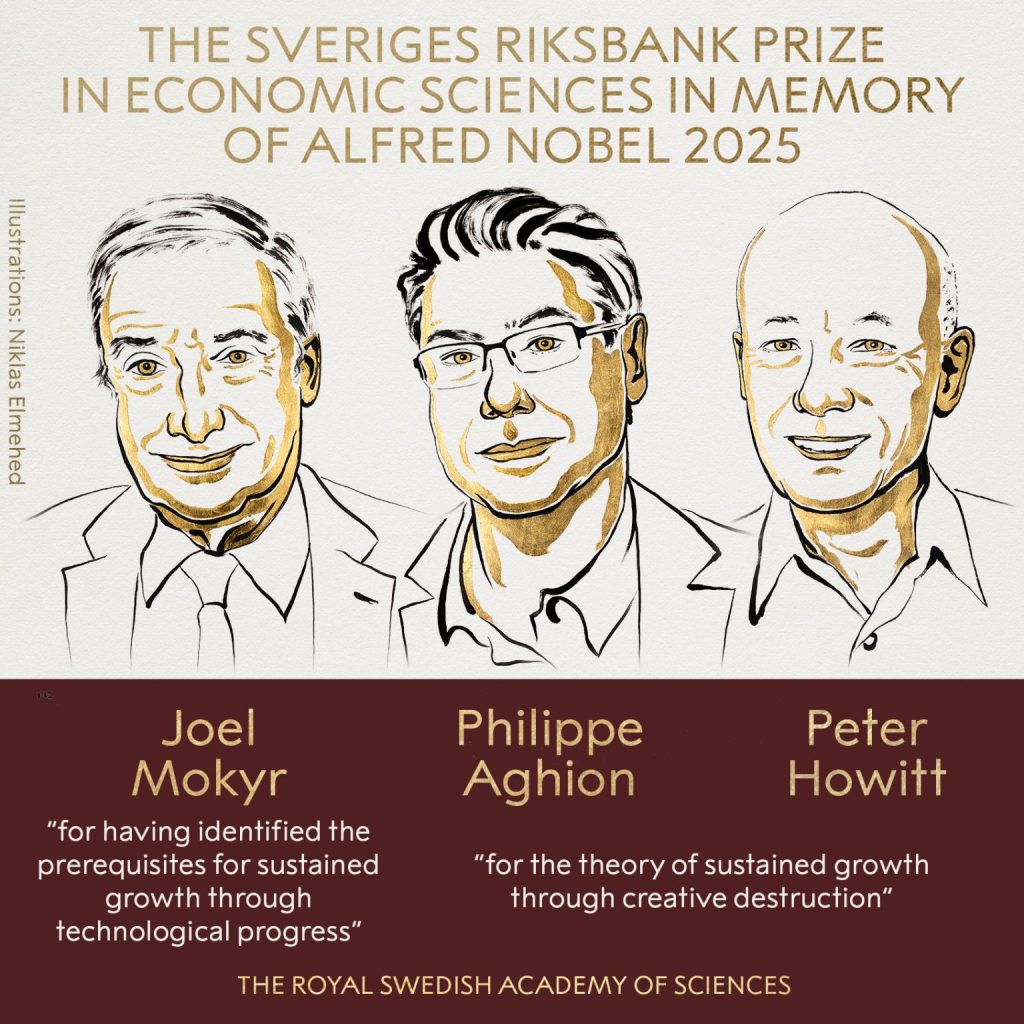

The 2025 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences recognizes Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt “for having explained innovation-driven economic growth”. At first glance, the selection may look like yet another tribute to growth theory. But digging deeper into their combined body of work and its modern relevance, the award sends a powerful message: sustained, inclusive growth is neither automatic nor frictionless and in an age of accelerating technological change, we must rethink policy, social contracts, and institutional design.

What the Laureates Teach Us: Growth Is a Process, Not to Be Taken for Granted

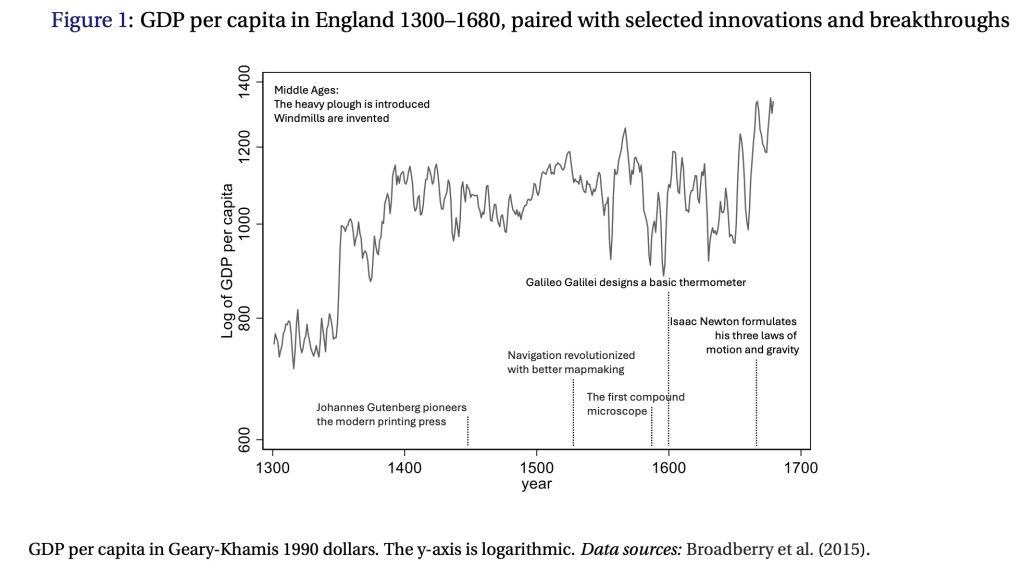

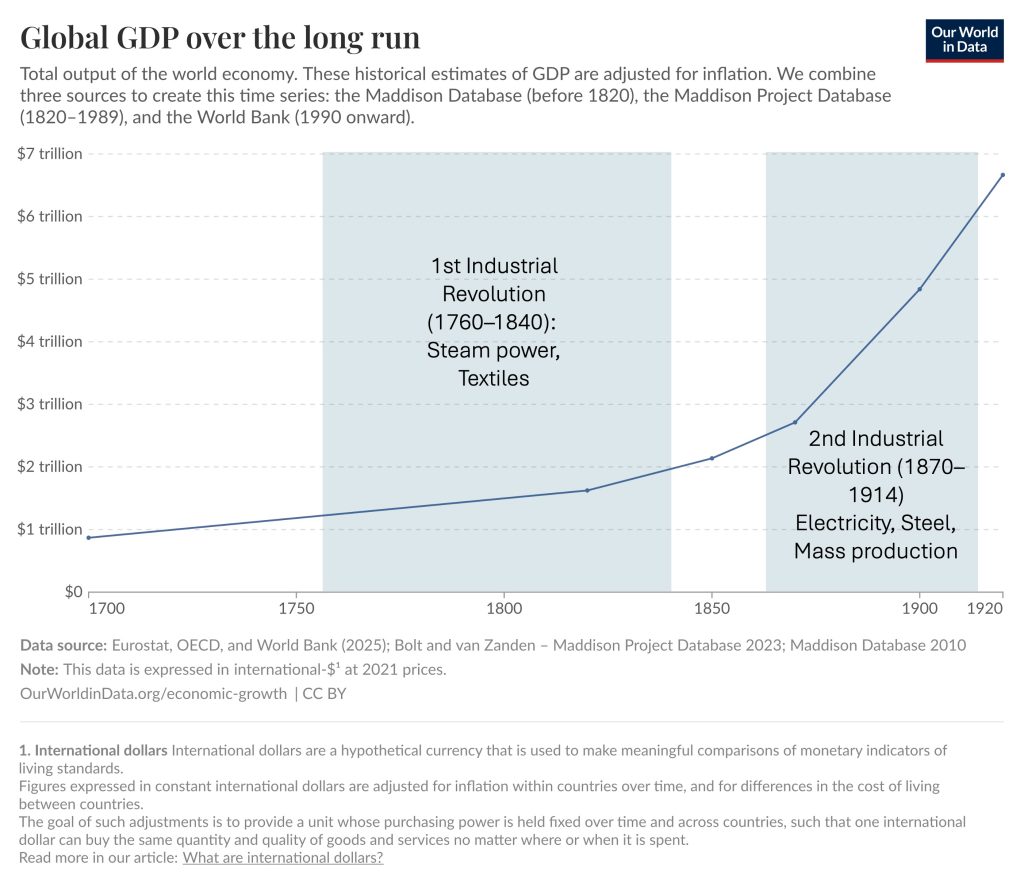

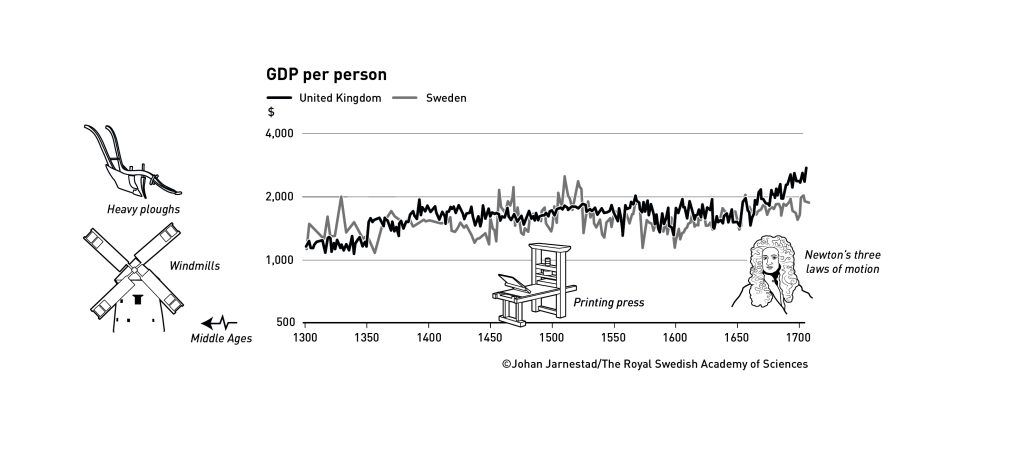

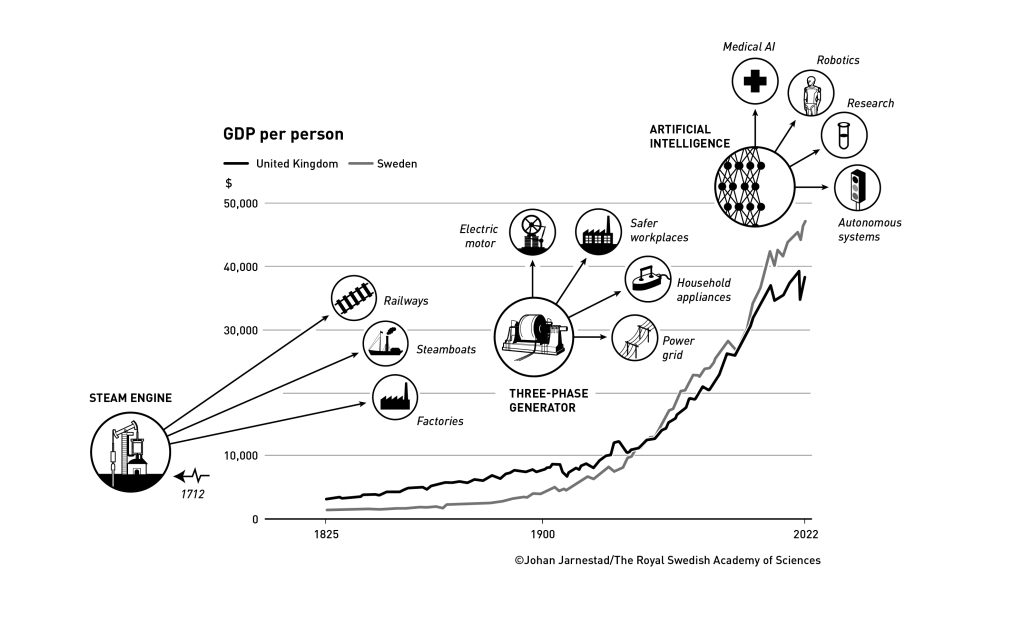

Historically, most of human experience was defined by stagnation or episodic progress. Until roughly two centuries ago, economic advancement rarely persisted across generations. The laureates’ work helps explain how the world moved from this “pre-growth” regime into what we today consider the “new normal”, as persistent and innovation-driven expansion.

Joel Mokyr’s contribution lies in tracing how useful knowledge, a symbiosis of propositional (scientific, theoretical) knowledge and prescriptive (practical, implementation) knowledge, became the engine of a self-reinforcing growth trajectory. Before the Industrial Revolution, technical experiments often failed to translate into scalable change precisely because underlying scientific understanding was weak or not systematically connected to practice. Mokyr shows how the Enlightenment and institutional openness gradually broke this barrier, creating a positive feedback loop between science and application.

Aghion & Howitt formalize the notion of creative destruction. Their 1992 model posits that economic growth is driven by successive waves of innovation, each new entrant displacing older firms, products, or methods. They embed this process into a general equilibrium framework, revealing tensions (e.g. between incumbents and entrants, between private incentives and social returns) and policy levers (R&D subsidies, competition policy, patent design) that influence the pace and distribution of growth.

Together, Mokyr’s historical and conceptual framing and Aghion–Howitt’s formalization offer a more complete narrative: growth is not a passive byproduct of factor accumulation, but a dynamic process that depends on institutional conditions, openness, conflict resolution and incentive structures.

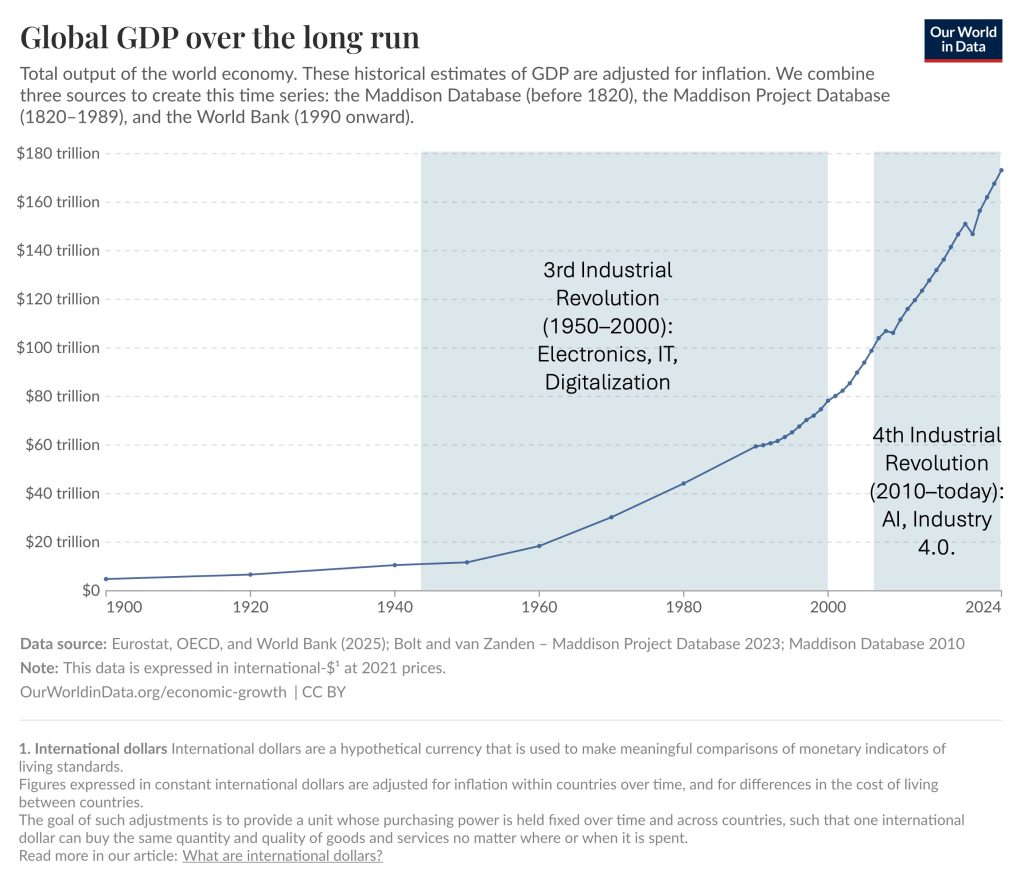

Relevance in the Era of AI: Growth Under Disruption

The timing of this award is particularly salient given the rise of artificial intelligence, generative models, and transformative digital technologies. The laureates’ insights help us interpret not only how past growth emerged, but also how we might manage future transitions.

- Reinforcing knowledge feedback loops. Mokyr’s framework suggests that when propositional and prescriptive knowledge interact closely, innovation becomes cumulative and self-sustaining. AI, with its capacity to accelerate scientific discovery, automate translation of theory into prototypes and generate new insights, may strengthen this feedback loop. We may be entering a phase where the pace of useful knowledge accumulation accelerates in non-linear ways.

- Intensified creative destruction. Aghion & Howitt warn that innovation inherently displaces incumbents and the more radical the innovation, the greater the disruption. AI-driven change may intensify this process, making entire industries or occupations obsolete at an accelerated rate. Thus the challenge is not whether disruption will come – it’s how society accommodates it.

- Conflicts and resistance. As firms and vested interests lose ground, they may resist change, lobby for regulations or protection, or slow the diffusion of new technologies. The Nobel laureates emphasize that conflict management is integral: institutional and political mechanisms must allow change to proceed while mitigating social dislocations.

- Limits, externalities and sustainability. Acceleration of growth doesn’t guarantee benevolent outcomes. Technological change can bring negative externalities – environmental degradation, inequality, job polarization, displacement, concentration of monopoly power and threats to democratic accountability. Mokyr, in his reflections, cautions that growth isn’t always sustainable without policy correction.

Thus, the laureates’ work should spur reflection not only on growth but on how growth is sculpted. The design of institutions, redistribution, regulation and resilience become central concerns.

Key Policy and Institutional Lessons

From the laureates’ theories and the current technological landscape, we can draw several actionable lessons:

- Cultivate institutional openness and intellectual freedom. Growth requires societies that tolerate dissent, accommodate new ideas and limit capture by entrenched interests. Barriers to entry – regulation, intellectual property, restrictive licensing, cartelization – can obstruct the innovation pipeline. Historical evidence suggests that openness to intellectual pluralism was central to the industrial enlightenment and the growth transition.

- Balance competition and stability. Innovation benefits from both experimental risk-taking and institutional safeguards. Too much market concentration or dominance by a few tech giants may stifle downstream innovation. Too much instability may discourage investment. Policies must manage this tension: antitrust, open standards, platform regulation and thoughtful patent regimes have a role to play.

- Subsidize knowledge spillovers. Because the social return on new knowledge often exceeds the private return (owing to spillovers and cumulative learning), optimal growth trajectories frequently justify public support, such as, R&D grants, tax credits, collaborative platforms and public research institutions. Aghion–Howitt’s framework clarifies when and how much support is socially optimal.

- Support human capital, mobility and adaptive institutions. In a volatile innovation regime, workers will need continuous reskilling, mobility across sectors and social safety nets that guard people, not jobs. The concept of “flexicurity” (labor flexibility plus security) becomes especially relevant.

- Monitor and manage systemic risks and externalities. Technological growth may generate climate pressures, resource overuse, algorithmic biases, concentration risk and social fragmentation. Governments and institutions must govern innovation, ensuring that growth is sustainable, ethical and inclusive.

- Mind the geopolitical dimension. In a world where leading-edge AI and biotechnology confer strategic advantage, growth is not purely a domestic concern. Nations must balance openness with security, protect core capabilities and avoid zero-sum rivalries that inhibit global knowledge flows.

What the Nobel Prize Signals and What It Calls Us to Do

This year’s Nobel Prize is more than an academic salute. It is a call to action, a reminder that growth is fragile, contested and institutionally mediated. If we think of AI, climate tech, biotech, renewable energy or next-generation manufacturing as potential engines of progress, their promise will only be realized in an ecosystem that manages conflict, rewards experimentation, stewards transitions and shares gains broadly.

In particular:

- Developing economies must pay attention. The lessons on creative destruction and knowledge diffusion are not just for high-income countries. Institutions that resist change or entrench elites risk foregoing growth opportunities or being left behind in the AI era.

- Policymakers and technologists should not operate in separate silos. Technological foresight without institutional design is brittle; institutional rules without technical literacy may be blind. Cross-disciplinary collaboration is essential.

- Civil society and labor organizations are vital participants. The force of disruption will be felt in the labor market. Institutions for retraining, social safety nets and voice will determine whether growth remains inclusive or exacerbates inequality.

- Business leaders and investors must internalize that innovation strategy is deeply political. They should consider that sustaining growth requires tolerance for disruption, reinvestment and engagement with regulation.

- Academics and universities should renew their commitment to bridging the “two cultures” of science and application. That bridging is precisely what Mokyr calls for and what today’s challenges demand.

Concluding Thoughts

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics honors intellectual depth, historical insight and theoretical rigor. But its deeper value lies in the questions it reopens: growth is not guaranteed; it must be engineered. The turbulence of the AI age will test the resilience of our institutions, the legitimacy of our political economy and the inclusiveness of our progress.

Innovation, so often framed as a technical or market matter, is in truth a fundamentally political and institutional challenge. The laureates’ work equips us with a sharper lens through which to view that challenge. Their message compels us not just to cheer breakthroughs, but to build the supporting systems that allow breakthroughs to endure, diffuse and uplift.

In that spirit, the true measure of this year’s prize may rest not only in which models are cited in future research, but in how societies act on its lessons. The task ahead is the collective responsibility to turn these lessons into action that secures inclusive and sustainable growth.

References:

- https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2025/press-release/

- https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2025/popular-information/

- https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2025/10/advanced-economicsciencesprize2025.pdf

Figures with GDP and Creative Destructions 1300-2025

Fatmir BESIMI

Professor of Economics, South East European University, North Macedonia.

Founder and CEO of Strategers.